Dunhuang and thereabouts

Photos from a trip to Dunhuang in May 2021.

So why would you want to go to Dunhuang?

Dunhuang is an ancient oasis town on the Silk Road, with scenic and historical sites to see in the surrounding area. And camels!

On the list for this visit: Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Lake, the Mogao Caves, Yumenguan, the Yulin Caves, Suoyang Ruined City, and a camel ride for Little H.

What’s in this post?

Dunhuang

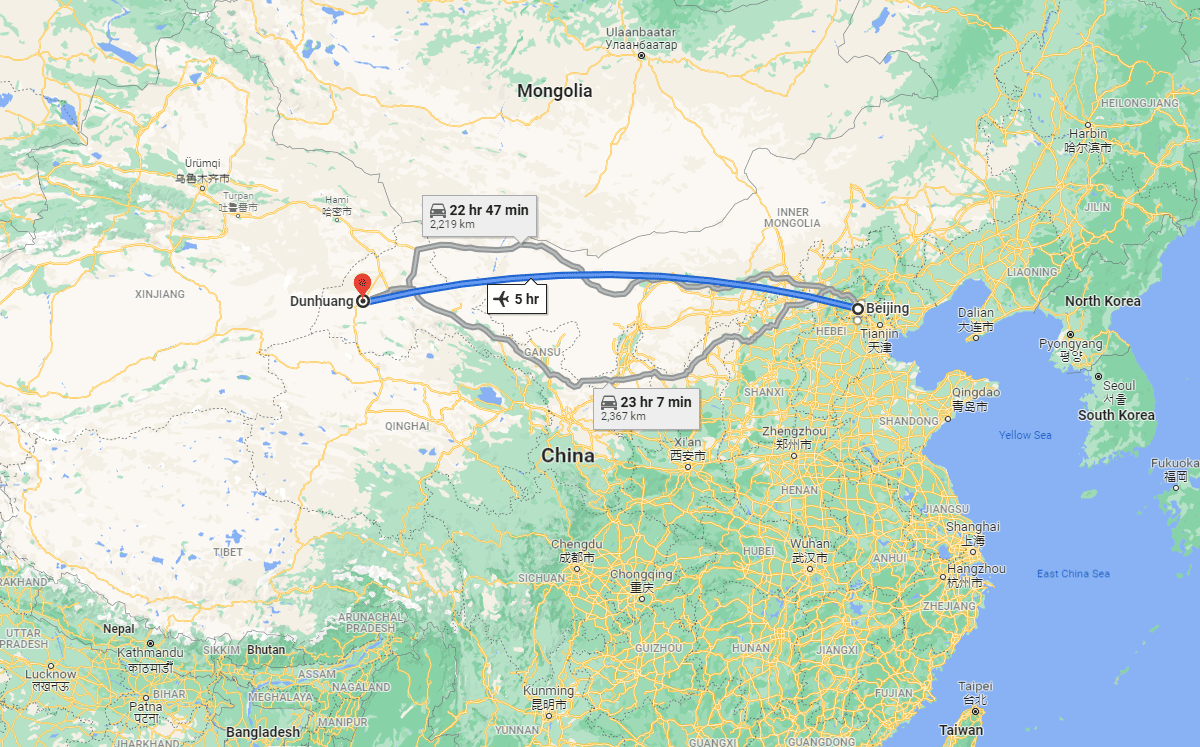

Dunhuang is located in Gansu Province, about 2,000km west of Beijing. It’s a small-ish town by Chinese standards, with a population of maybe 200,000.

Both the northern and southern Silk Road routes around the Taklamakan Desert went through Dunhuang, and it was one of the main four early Han Dynasty frontier garrison towns. It was the last stop heading west before getting really out there. (‘Early Han Dynasty’ means about 100 BC, and those four frontier towns were Dunhuang, Jiuquan, Zhangye, and Wuwei. Read more about Dunhuang on Wikipedia)

The desert comes right up to the edge of town, with huge sand dunes rising up over the outskirts on the south side.

Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Lake

As a Quintuple-A-rated Tourist Attraction, the Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Lake Scenic Area is extremely popular with tourists, despite there not really being that much to do there.

The lake is indeed crescent-shaped, and is under management to prevent it from drying up. The sand dunes are impressively tall but are mostly off-limits ‘to protect the environment’.

You see the lake, you climb the dunes, you take a microlight flight (if you dare). And you ride a camel! The plan was to get Little H on to a camel, and maybe watch the sun set over the lake. And the plan worked, but being so far west we had to wait until 9pm Beijing time for sunset.

Mogao Caves

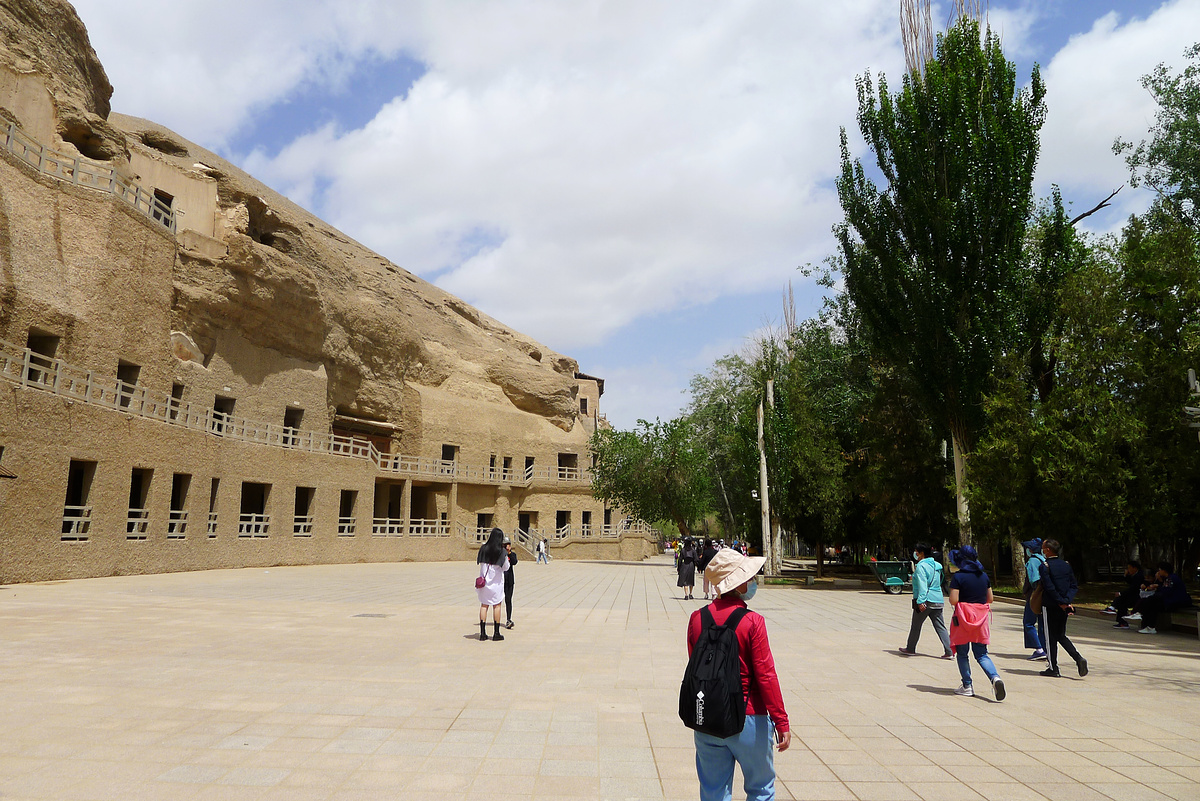

The Mogao Caves were cut out of a cliff by Buddhist monks, starting around 366 AD. The caves were initially used as a place to meditate. Some caves were used as shrines, and as time went by sculptures, statues, and murals were added, “the cave paintings and architecture serving as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform those illiterate about Buddhist beliefs and stories.” (More about the Mogao Caves on Wikipedia)

My first visit here (2011) felt magical; this time not so much. But I’d say that was because of language issues. On that first visit we had the tour in English. This time I tagged along with a Chinese group. My Buddhism-and-caves Chinese vocabulary is not extensive, and being able to understand more of what the guide is talking about makes it a much better experience. Little H was more interested in a chocolate icecream in the shape of the fore-temple that houses the Great Buddha (see below) and there was a thunderstorm on the way, so this turned into a quick visit.

(Photography of the insides of the caves is forbidden; please enjoy three photos of the outsides.)

The Mogao Caves Visitor Center shows a mini-documentary that shows the scale of the Great Buddha behind the fore-temple—rather gigantic!

Yumenguan

The Silk Road continued through Yumenguan – ‘Jade Gate Pass’ – which was the last major fortification beyond Dunhuang. What’s left there now has three main parts: rammed earth Han Dynasty Great Wall, the ‘small’ Fangpan Castle, and the ‘big’ Fangpan Castle.

Back in the day you had to travel for weeks to get here from Dunhuang. In more recent times it still took at least a day, because there was no real road—just short concrete posts marking a route that you could theoretically follow through the gravel desert. Those posts are still there, beside the new highway.

This was on my places-to-visit list as the ‘westernmost part of the Great Wall’.

Yulin Caves

The Yulin Caves are similar to the Mogao Caves, but smaller. They’re located near Guazhou, about a two-hour drive from Dunhuang. The caves here were carved out of the cliffs between the seventh and fourteenth centuries AD.

To get here you first drive to Guazhou, and then out into an alluvial plain. Beyond the plain are snowy peaks; part of the Qilian Mountain Range, on the edge of the Qinghai Plateau.

The road begins to run alongside a river that cuts through the plain, the cut deepening into a canyon, with the blue water of a reservoir some of the only colour in the landscape.

From a carpark on the cliffs of the canyon you can look down to see the bright green of elm trees by the side of a river that’s fed by snow-melt and whatever little bit of rain the area gets. The elms are the only green seen for nearly an hour, really, and they’re hidden inside the canyon, as are the caves. The Chinese word for ‘elm’ is ‘yu’, and this is where the name of the caves comes from. (‘Yulin / 榆林’ means ‘Elm Forest’.)

We paid extra to include the ‘special caves’ on the tour. Little H declared the caves too scary shortly after entering the first. While HJ had the full tour of the special caves Little H and I spent extra time playing about outside.

The Yulin Caves were on my places-to-visit list in the ‘Buddhas in caves’ category. I’m a big fan of the whole Buddhas-in-caves vibe.

While HJ was on that tour of the special caves Little H modelled a backwards jacket and made up games with pebbles.

Suoyangcheng Ruined City

Not too far – by car – from the Yulin Caves is Suoyangcheng Ruined City. Like Dunhuang, the city dates back to the early Han Dynasty. The city was ruined by a Mongolian attack in the sixteenth century, and the main things to see here now are the remains of Ta’er Temple (said to have been visited by Xuan Zang on his journey to the west), and the rammed earth remnants of the city walls, which are slowly being covered by sand.

For your entry fee you get a circuit of the city in a golf-cart type vehicle.

Liugong Ruined City

This site is similar to Suoyangcheng but is much smaller and maybe mostly forgotten about. Getting here involves a detour off the highway to Dunhuang and on to a bumpy narrow dirt road by the side of the irrigation canal that feeds the fields that surround what’s left of the city walls. Supposedly the Silk Road went along in the foothills just on the other side of the highway.

Miscellaneous

- The WFH (Work From Holiday) plan was slowed by equipment failure, and that meant there wasn’t much opportunity for looking around regular Dunhuang.

- We switched hotels each night. (The first was expensive, the second had bugs.)

- There aren’t many flights in and out of Dunhuang. We booked on a smaller airline to avoid a super early departure from Beijing, and on the way back got stuck with a two-hour flight delay at a stopover at some tiny airport somewhere in the middle of I Don’t Know Where in eastern Gansu.